8. They Don’t Have To Make Fallout (or) The Merits of a Spiritual Successor

Feargus Urquhart has mentioned his fervent desire for Obsidian to work on a new Fallout game, including New Vegas 2. But I suspect that if any Obsidian staff are reading this, there may be a part of them thinking about the complications that presents.

Specifically, the relative lack of freedom in order to conform to Bethesda’s view of Fallout: there’s no way for them to change much of the status quo in that world, drastically alter core aspects of the gameplay in their own way, or move the story further ahead in the timeline. Doing so might interfere with the production of Fallout 4, and those limitations must, understandably, be in place.

Couple that with the eighteen month development time for Fallout: New Vegas (compared to the four years spent developing Fallout 3), you can see the potential frustration present in such a proposal.

Licensed games, of course, have always had that limitations: but in a franchise that had been a part of their lives as developers for so long, I can imagine a much greater desire for control over Fallout than they would have for the upcoming South Park: The Stick of Truth.

But, as I said, they don’t have to make a Fallout game.

Earlier, I mentioned Troika’s efforts to create a post-apocalyptic RPG of their own. During its prototype development, Troika co-founder and Fallout designer Leonard Boyarsky said:

As far as overall feeling of the game, we’d really like to capture a distinctive mood and style like we were able to in Fallout. Whether this will be similar to Fallout’s style and mood or something totally different is not something we want to discuss yet. From a gameplay/system perspective, this game is definitely a spiritual successor to Fallout.

Obsidian could do that too. Developers have been doing it for decades when the publisher is unwilling to relinquish the property, the team dissolves, or a key creative staffer moves to another company. There’s even a name for this kind of design: the spiritual successor. Whether it’s design choices, writing, the setting, or outright gameplay, it creates a new, but familiar experience for players who enjoyed the original title, while still improving on what came before.

Let’s look at a few examples:

Fire Emblem – Tear Ring Saga

Total Annihilation – Supreme Commander

System Shock – Bioshock

Final Fantasy – The Last Story

Planescape Torment – Knights of the Old Republic II: The Sith Lords

Wasteland – Fallout

That’s right: For those of you not in the know, after Electronic Arts published Wasteland, Interplay was unable to get the rights to develop Wasteland 2. It was from this that a post-apocalyptic RPG was put in to development at Interplay, taking design cues (open world, the setting, choice and consequence oriented writing, and certain elements of the dialogue in particular) from the original Wasteland. However, the gameplay, setting, and methodology behind the storytelling was revamped, creating a fresh experience that improved upon the elements that made Wasteland such a beloved title.

In the cases of these spiritual successors, each of them acclaimed in their own way, you can see that it wasn’t the setting that made them successful: It was the people behind them. With the utilization of new and different design choices, the titles managed to create a fresh but familiar experience, beloved in their own right rather than as just extensions of their predecessors.

The reason that spiritual successors are often necessary isn’t because of a lack of interest in the original title, rather, it’s because game developers generally do not own the rights to the content they create. In the case of major game development, they make pitches to the publisher the same way a director or screenwriter does to a studio.

If the pitch is accepted, the publisher will fund the game’s development, distribution and marketing costs in exchange for the intellectual property rights, the majority of the profits, and a say in how the game is developed.

Now, this series isn’t intended to rail against the evils of publishers. After all, a similar system has been employed by television, comic strips, comic books, and movies since the inception of their mediums. And given the choice between the developers at Obsidian working on a Fallout game, or a new intellectual property set in a post-apocalyptic world, I would be tempted to pick Fallout.

But they don’t need the Fallout license to create a good game in that vein. The SPECIAL system, combat, and the setting itself aren’t why people love the series. If that were the case, Fallout Tactics would be looked at far more fondly than it is. It’s the reactivity, consequences, tone, the way you shaped the world with your presence, and the voices of talented developers that make Fallout, if you’ll pardon me, special.

Bethesda can provide Obsidian with a license to the setting, and the funding to develop the game. The profits for a spin-off title on the PC could be theirs. But if the setting isn’t necessary to create a new title that kept the things that make Fallout great, if there is an additional freedom to be gained by using a property that Obsidian owns outright, that leads only the question of funding – and if Bethesda is needed for that at all.

9. Kickstarter

I suppose it had to come to this, didn’t it?

I’m not going to run over the merits of kickstarter and crowdfunding in general as a concept, either as a whole or specifically as it relates to the gaming industry. Talking about it would entail my discussing developer/publisher relationships, the horrors of crunch time, intellectual property rights, inflated budgets in the gaming industry due to bleeding-edge technology, my frustration with Metacritic, and so much more.

What I will talk about, however, is what it is allowing developers to do. I mentioned before that movies, television, comics, comic strips and gaming were handled the same way: The creator of the property generally does not hold the rights to said property. I hold no malice towards the system, and I hope to enter one of them someday. But when I look to kickstarter, I see it as an opportunity for something that has not always been readily available: independently created content that might not otherwise have mass appeal.

Mass appeal is the operative phrase when it comes to kickstarter. Imagine my shock when the new Tomb Raider, which holds a Metacritic score slightly higher than Fallout: New Vegas, sold 3.4 million copies (not counting digital sales) – and was considered a failure.

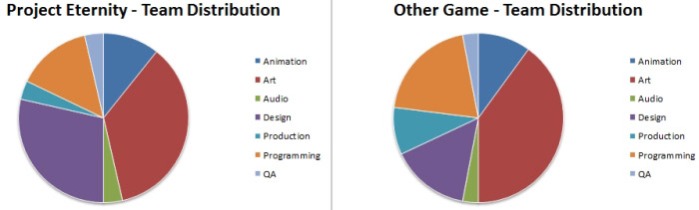

But Obsidian Entertainment isn’t Square Enix, they’re a medium-sized developer. This is a big part of why Project Eternity, a game which appeals to those who played a style of RPGs which largely stopped development after Icewind Dale II, is a workable model.

The entirety of Project Eternity‘s development costs have been funded at $4.3 million, from (roughly) 75,000 backers. The developers have been paid, and every copy that is sold upon launch is effectively profit: there are no more costs related to development to cover.

And even if they sold another 75,000 copies at a theoretical budget price of $30, it would generate $2.25 million in income for Obsidian – a little more than half of Project Eternity‘s final budget.

Obsidian has already promised an expansion pack for Project Eternity to be developed without using their kickstarter’s money, and expressed their desire for full-on sequels. It’s unknown whether these sequels were self-published through the profits from Project Eternity or funded through kickstarter, but the scope for what they consider a success, and what they’d need to continue the franchise, is vastly different than that of a big publisher.

When you add together the idea of lateral thinking with withered technology and the concept of spiritual successors, you get a better understanding as to why crowdfunding has been successful for gaming. The most successful gaming campaigns are, for the most part, either licensed sequels or spiritual successors to past games. Torment: Tides of Numenera, Project Eternity, Wasteland 2, Shadowrun Returns, Shroud of the Avatar, and Broken Age being just a few of the bigger names.

You could claim that these successes are born wholly from a sense of nostalgia or brand loyalty, but I disagree. I donated for a boxed copy of Wasteland 2 without ever having played Wasteland, the original Fallout titles, or any inXile game – nor am I much of a PC gamer. I was simply fascinated with the prospect of playing this kind of game.

There is, of course, another option. It worked for Veronica Mars, Leisure Suit Larry, and Shadowrun Returns: License the property to Obsidian for one title and let them do a kickstarter to fund it. While such propositions from publishers were offered to Obsidian, they were all related to new IPs, not a license. A Fallout title would give Bethesda the best of both worlds – minimal investment, and the profits from what I believe would be a great game.

And no matter how it was funded, for newer fans who only know Fallout 3 and Fallout: New Vegas, I suspect there are more than 75,000 of them with an open enough mind to take a look at something new.